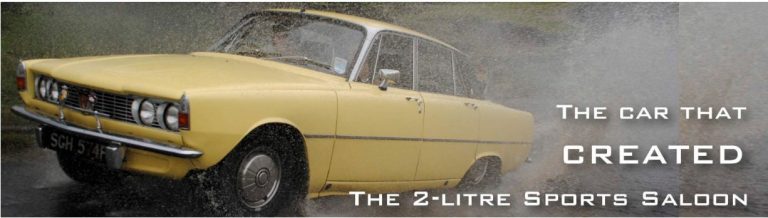

The Rover P6

Probably the most technologically accomplished saloon car the British motor industry has ever produced, the Rover P6 is the defining sports saloon of a generation. With performance, style and safety in equal measure, it is one the most innovative and attainable performance classic cars you can buy today.

Rover 2000

Launched in 1963, the Rover Two Thousand was a low slung, sporty, saloon car packed with novel features such as engineered crumple zones, power assisted disc brakes on all four wheels, and a radical independent suspension specifically designed for radial tyres. Many other safety and convenience features fitted as standard were years ahead of the competition.

The result was the initiation of a new market sector, the 2-litre luxury sports saloon, typified these days by the BMW 3 Series; the award of the first ever European Car of the Year in 1964; and numerous awards for safety during its lifetime. The 2000 arrived with the bright grille, flatter bonnet, and simpler flanks of the Series 1 cars. In 1967 the automatic appeared, followed shortly by the Twin Carburettor version, at which point the badging was changed to 2000 SC or 2000 TC. In late 1970 (1971 Model Year) all cars received the Series 2 facelift of black grille, “V8” bonnet with badge, and side strips.

The SC Automatic and TC were offered as a Federal specification in the US and Canada between 1968 and 1969, and the TC again in 1971 following the facelift.

Rover 2200

In 1974, the 1,978cc 4-cylinder engine was bored out to 2,205cc to become the Rover 2200. It remained available in SC, SC Auto and TC forms and all cars were Series 2 facelift style.

This larger capacity gave buyers an increased power output, alongside much improved low-end torque. All with little compromise to fuel economy.

Although perhaps not recommendable today, a 2200 is well known to cruise happily at 90mph and the TC model provides owners with a good turn of speed.

Rover 3500

In 1968, the famous, Buick derived, Rover V8 was fitted to the P6, following its debut in the P5 a year earlier. The P5B was badged Rover 3.5, so the P6B became the 3500, described as “Three Thousand Five”.

Initially in the Series 1 shape, with a bright finisher and V8 badge on the front of the bonnet, the engine was only available as an automatic, offering smooth, effortless performance.

Like the 2000, this model was facelifted to series 2 in 1970, then in late 1971, the 3500S was offered, with a manual transmission and an extra 6 BHP. Tested by Autocar at launch the top speed was more than 120 MPH.

The 3500 was also sold as a Federal specification from 1970-1971, confusingly badged 3500S, even though they were all automatics.

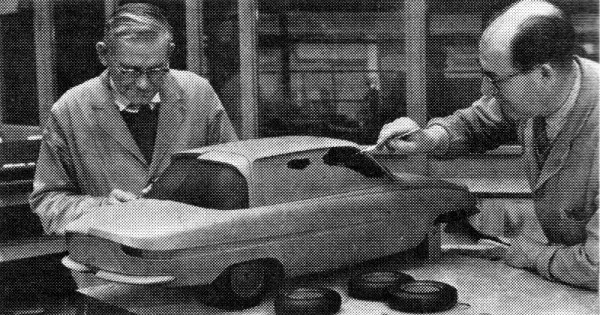

Taking motoring years ahead

When the earliest planning sessions for a lightweight, compact and modern saloon began in the office of Robert Boyle at Solihull in late 1956, none of those present could have known that it would take seven years to bring the car to market. But the product (codenamed Rover P6) that eventually emerged as the Rover 2000 in late 1963 was a revolutionary reimagining of the saloon car. It was that most rare thing in the British motor industry – an entirely new introduction. Every element of the Rover P6 from the ground up was new and designed at great expense to perfectly meet the requirements and expectations of its designers.

The Rover Company was perhaps Britain’s most conservative car producer. The upright P4 ‘Auntie’ Rover and new 3-litre P5 were the symbols of the established middle-classes, and all were virtually hand-built on slow-moving production lines with traditional craftsmanship. Very little of the technology and engineering was new or radical, but rather followed the German principle of continually developing a successful recipe to create an ever more refined expression of a motorcar for a small, exclusive market with very high expectations.

And yet from this most conservative company came a car that was so radical, so bold, and experimental, that it redefined the concept of luxury motoring and fundamentally transformed the saloon market in Britain. Today, the German contingent of low, sporting, luxurious BMWs, Audis and Mercedes-Benzes dominate the British car market. They offer access to a high-end luxury and sporting motoring experience in a compact saloon package that is reasonably affordable to a large section of the market. These cars are the direct spiritual successors to the Rover P6, which was the creator of this market for Britain.

The founding principle of the Rover P6 was to offer the performance, refinement, and quality of a traditional British luxury saloon, but with the economy, size and affordability of a much smaller modern car. The key to achieving this was intelligent design. By embracing new technologies and developing a sophisticated lightweight engine and transmission, the same level of performance was achieved with 2-litres instead of 3, and four-cylinders instead of six. This in turn meant lower purchase tax and lower overall running costs, thus opening the Rover P6 to a much larger and more fertile buying market. Ultimately, this would generate a much higher demand for the cars, and volume production gave access to financially favourable economies of scale to both justify the huge expense of developing the car and allow a remarkable list price of just £1200 instead of the £1800 commanded by a usual luxury saloon.

This was a huge gamble to develop a car for which there was as yet no obvious market. Rover invested an unprecedented £10.6 million of Land Rover profits in creating a saloon that was entirely new from the ground up – compare this to the £2 million required by Jaguar to develop the Mk2 saloon and the scale of Project P6 becomes evident. No new technologies were considered too radical to be incorporated into the design, no ideas too experimental, and there was as much thought given to the production and assembly processes as there was to the design of the car itself.

Aware that the Rover P6 would not be financially justifiable without volume sales, but equally mindful that quality had to be consistent and high for the car to command its list price, Rover devised ground-breaking production techniques to ensure consistency and quality throughout the production cycle. These methodologies were decades ahead of the British rivals and paralleled the best of contemporary European car producers. Robotic electro-static paint spraying – a British first – was devised to paint the panels before they were bolted to the car, guaranteeing quality, longevity, and consistency of finish with very little waste. Every base-unit went through a full-immersion effective phosphate rust proofing process, and a robotic jig precision drilled and tapped the threads on every base unit so that misaligned mounting points – and time-consuming rectification work – were eliminated. Even the design of major components like engines were divided up in such a way to make each individual component as straightforward to produce as possible to ensure consistent performance when assembled. The raw castings of cylinder heads and blocks, for example, required just two flat facing cuts in a milling machine to prepare them for assembly, instead of the usual complex, labour-intensive and manual processes required to machine hemi-spherical combustion chambers – a process which carried an inevitably high failure rate. It was this emphasis on quality, consistency and intelligent design throughout the production cycle that allowed Rover to produce a staggering 900 cars per week and access the financially viable economies of scale to justify the huge cost of the impressively modern and unique technology that underpinned their new car.

The Rover 2000 took seven years to make the journey from memo to production, and at its launch was arguably the most radical and advanced engineered car in Britain irrespective of price. Once complete, the Rover P6 went through new crash-testing techniques which were developed and studied, cars were extensively tested through over half-a-million miles in all climates and countries, there was an absolute focus on safety, and performance and handling was a decade ahead of the competition.

The resulting car, the Rover P6, is one that is so beautifully free of inherent design compromise that it ranks as one of the greatest achievements of the British motor industry.

Radical technology meets refined sophistication

The Rover P6’s radical independent suspension design remains unique to this day. A deDion configuration at the rear had previously been seen only on Italian racing cars but was now redesigned and modified by Rover specifically to cure lift-off oversteer and facilitate the use of new-fangled radial ply tyres. The front suspension employs a deeply unconventional double wishbone setup with the top links arranged at 90 degrees to the lower and incorporating a bellcrank to locate the springs horizontally above the top links to place the suspension load directly onto the bulkhead – the strongest point of the car. The original purpose was to make the engine bay as wide and un-intruded as possible to allow the fitment of the Rover jet engine (below) – a prospect Rover genuinely believed to be a viable and realistic alternative motive power source by the end of the decade.

Sadly, the jet car project was never pursued beyond a few prototypes, but the advantage of the design was a front suspension that eliminated pitch and dive under hard braking/accelerating, generated impressive camber change for fast bends, and collapsed safely on impact as the inner wing crumple zones folded. Long travel coil springs and telescopic dampers all round make for a sublime ride quality with impressive noise and vibration suppression – even by today’s standards.

Power assisted disc brakes on all four wheels – inboard at the rear to reduce unsprung weight – were a breakthrough that was unheard of on a compact 2-litre car. The well-weighted steering box gives positive feedback and won’t move in a head-on collision, and the short gearlever gives a crisp and positive change that makes for a driving experience which rivalled the best of Britain’s performance GT cars.

The original four-cylinder Rover 2000 engine was a triumph of intelligent design that embraced new technologies and production techniques to deliver the performance of a much larger engine with fuel economy that bettered many of its contemporaries. Lightweight aluminium alloy was used extensively in the engine and gearbox, and the cast iron cylinder block is ‘skeletal’ with large windows in the sides covered by thin steel plates to reduce weight. A two-stage duplex roller chain drives an overhead camshaft which acts directly onto the vertically inclined valve-gear through bucket tappets, eliminating the need for inefficient and noisy rocker arms. The cylinder head is flat, and on the Rover 2000 models, the pistons have a deep dished ‘heron’ crown creating an inverted hemi-spherical chamber for effective combustion. This very distinctive combustion chamber design and valvegear arrangement bears striking similarity to the legendary 5.3-litre Jaguar V12 of 1971, and is probably the inspiration for the Jaguar design, which had abandoned twin-cam hemi-heads late on in development in favour of a single overhead cam ‘heron head’ design which came seemingly from the blue.

Redefining the saloon

The original Rover 2000 TC models were developed before the introduction of the blanket 70 mph motorway speed limits and were designed to achieve the highest possible top speed for a market in love with speed. The engine was therefore designed to rev high – a characteristic that was comfortably afforded by the direct overhead camshaft arrangement and uncommon square bore/stroke proportions. All Rover 2000 TC models were also given racing standard breathing: a four-branch tubular header exhaust system was fitted as standard to complement a water-heated ported inlet manifold with twin 2-inch SU carburettors – the largest carburettors ever fitted to a British production car, and shared only with the likes of the E-Type Jaguar, Aston Martin DB5 and Austin-Healey 3000. The result was a hard-revving, thrashy, hairy chested driving experience with a sublime exhaust note. High compression pistons took advantage of the highest octane 5-star fuels of the day, and a well sorted Rover 2000 TC could hit 115 mph – just 10 behind the Mk2 Jaguars, the fastest production four-door cars in the world in the mid-sixties. But unlike the 3.8-litre Jaguars, the sophistication of the Rover design accessed this sort of speed with just 1978cc.

It is in the driver’s seat that the magic of the Rover P6 becomes obvious. From this position, the relentless attention to detail and uncompromised emphasis on quality, refinement and safety converge to create one superbly comfortable and responsive driving experience.

The body-hugging medically-designed seats and evocative thin-rimmed steering wheel are fully adjustable for comfort. The driver controls fall perfectly to hand and operate with short, crisp movements. You sit low in the body with the bonnet stretched out ahead of a wraparound windscreen giving exceptional forward vision. In later cars, the switches and instrumentation are softly back-lit in the kind of ‘Brave New World’ neon green you expect to see in a Stanley Kubrick film. It has some of the first multi-function steering column stalks, an effective and innovative variable wiper system, and the ‘S’ spec instrument pack found in series 2 Rover 2000 and 2200 TCs and Rover 3500s is built on a printed circuit board – a world-first.

All Rover P6 cars came with a pioneering ventilation system with infinitely adjustable heat and direction settings, face level air vents, blowers and effective demisters. Illuminated prisms on the front wings show the corners of the car so you can park in the dark. The first European Car of the Year award (1964), the first AA Gold Rosette for Safety (1967), soft-finish interior trim designed to crush on impact, child-safety door locks, an in-built stereo speaker system, hazard

warning lights, self-cancelling indicators, choke warning light, specially designed seat belts and orthopaedic head rests for all four seats, specifically engineered crumple zones, a self-filling 40-mile reserve petrol tank, and a warning light to tell you when your brake pads or fluid levels are low, are just some of the innovations that this ground-breaking car brought to the motor industry in its 14 years of production.

And there was luxury as well as innovation. Air conditioning, electric windows, power-assisted steering, automatic transmission, a full-length Webasto sunroof, ‘Continental touring kit’ placing the spare wheel in its iconic position on the bootlid, run-flat tyres (another world-first), deep-pile over-rugs, chrome Rostyle or wire wheels, fog lights, ‘Icelert’ cold weather detection system to warn of ice formation on the roads, heated windscreens, tinted windows, even a full-length tinted glass roof, were just some of the Rover P6 options available to the more demanding customer.

The Viking Flagship

In April 1968, Rover fitted their recently reengineered Buick-derived 3.5-litre V8 to the Rover 2000 body shell to create the legendary Rover 3500 (“Three Thousand Five”). The engine, which had been bought in its entirety including production tooling from US car giant General Motors, had been in development with Rover since late 1964 specifically for the Rover P6. Although the principal dimensions of the engine remained the same, it was extensively re-engineered by Rover in the interests of creating a smooth, refined and flexible power unit to replace the ageing inlet-over-exhaust ‘F-head’ six-cylinders of the later P4s and 3-litre P5 saloons.

Up until the arrival of the V8, a new six-cylinder based on the Rover 2000 engine had been in development. From the start, the Rover 2000 engine and production tooling had been devised as a modular design with the ability to be built as a 2-litre four-cylinder or 3-litre six-cylinder engine. All of the ancillaries for the Rover 2000 were deliberately located in a separate chain-driven housing at the front of the engine and it already featured a high-capacity oil pump. This allowed additional cylinders to be added to the rear of the engine simply by duplicating pistons and valve-gear, producing a different crank and camshaft, and casting longer blocks and ‘heads for machining on the same tooling.

The P7 (as the six-cylinder ‘Rover 3000’ project was known) had been developed to the running-prototype stage by 1964, but was immediately cancelled on the arrival of the V8 which offered a much more favourable power-to-weight ratio, and unlike the P7 3000 (which was originally planned to feature a longer restyled nose and alternative front suspension to give it its own unique character), the V8 could be fitted to the standard Rover 2000 engine bay with very few modifications, making it a much more cost-effective option.

The Rover 2000’s front inner wings and suspension lower link mountings were only modified slightly, and the front was subtly restyled with a deep valance and raised bumper. The Rover 3500 became a legend within its own lifetime, taking the helm from the retired Jaguar Mk2 as the defining sports saloon of its generation. The original models were designed to maintain Rover’s competitive presence in the 3-litre+ market where the coach-built P5 was insufficiently modern and built in too few numbers to compete with the influx of new, low, cleanly-styled performance saloons from the Continent, such as the BMW Neue Sechs and Mercedes Sonderklasse. As such, all early Rover 3500 models featured an automatic gearbox, and power-steering and other refinements could be specified to create an extremely luxurious, smooth, quiet and refined saloon.

The long-anticipated launch of the Rover 3500S in 1971 finally offered manual transmission on the V8-engined ‘Rover P6B’, albeit only a strengthened version of the Rover 2000’s 4-speed all-synchromesh ‘box with internal pressure lubrication. Trim levels were lower, vinyl roofs and Rostyle-inspired wheel trims were standard, and they were priced to sell. But with 60 mph coming up in 9 seconds and more than 120 mph on offer flat-out, it was impossible to go faster with four doors for less money, or less than 4-litres.

Up until that point, the manual-transmission Rover 2000 TC was sold as the ‘sports’ Rover P6 model. With performance that was very nearly as quick as the automatic Rover 3500, and superior handling thanks to the sophisticated and lightweight four-cylinder engine, they too are extremely desirable cars for enthusiasts today. So too are the over-bored Rover 2200 derivatives produced after 1973, which feature a usefully lowered compression ratio and modern carburetion for a much more flexible and less thrashy power delivery for today’s traffic.

Living with a Rover P6

Today, the Rover P6 in all its forms represents one of the most usable and practical classic cars for everyday motoring. Those developmental breakthroughs nearly sixty years ago make for a car that can shrug off the difficulties of the modern urban commute like perhaps no other vehicle of the period. Power assisted disc brakes on all four wheels, 50/50 weight distribution, a complex and advanced independent suspension, more than ample power, and ground-breaking passive safety innovations that were 20 years ahead of the mainstream, make it one of the best classic cars you can buy.

A well-sorted Rover 2200 TC is equally as fast as an automatic Rover 3500, and the trim levels are the same. What separated the models at the time was market positioning and list price What separates them today is character.

The four-cylinders are sophisticated and extremely well engineered cars that offer superior handling, modest economy and a very lively British ‘big four’ that can be stoked up to a hard-revving, thrashy, hairy-chested driving experience – a true sports saloon.

The V8 is an effortlessly quick long-distance GT car which offers supreme power and refinement in equal measure for a small compromise on design purity and sophistication.

Whichever Rover P6 model you go for; you will be the owner of a supremely well-engineered car that is optimised for its intended purpose. These are high quality luxury sports saloons, and trim levels were largely standardised across the range. The concept of a ‘base model’ for the fleet-car buyer had not yet been invented.

Parts availability is amongst the best of any classic, and with an active and vibrant support network through The Rover P6 Club, technical support and advice is as comprehensive as you can get.

The legacy

The Rover P6 was the last saloon car designed by the Rover Car Company Ltd, prior to being merged into British Leyland and its successor, the Rover SD1, was a much more conventionally engineered vehicle with a live rear axle and strut front suspension. So, was the Rover P6 an evolutionary dead end?

The Rover P6 (and to a lesser extent, the Triumph 2000) created the 2 litre Sports Saloon market with 328,000 Rovers and 195,000 Triumphs sold worldwide between 1963 and 1977. British Leyland failed to capitalise on this success in product planning, launching the larger Rover SD1 as a 3.5 litre car and when the 2000 “O” Series engine was fitted in 1982, performance was worse than the Rover 2200 TC. By comparison, BMW had produced a 2 litre derivative of the Neue Classe in 1965 and during the 1970s launched the 5 and then the 3 series and the rest is history.

The Rover P6 body construction, coil spring and disc brake knowhow and basic interior architecture (pod & shelf instrument panel design, and box pleat seating (for ventilation) were key ingredients in the highly successful Range Rover of 1969, a vehicle put together by much of the original P6 design team. The 1989 Discovery, based on the Range Rover platform used many of these elements as well.

Although the first car to use crumple zones was the much more expensive Mercedes W111 in 1959, the Rover P6 was the first car to use them in a smaller class of vehicle, at a time when most vehicles of any class would still cause major injuries in a severe impact. This feature, together with the non-intrusive (and adjustable) steering column are today taken for granted, but it was the Rover P6 that pioneered safety in an affordable car.

So many of the available features pioneered on the P6 (either directly or in its class) were benchmarked and offered on competitor vehicles over the years, and it is fair to say that the car has had a quiet influence on any modern car you drive today.

Under BMW, the Rover Group developed the Rover 75, which was a fine car for its time, but look closely, and many of the design cues are pure Rover P6 – the twin headlights, gently curving side profile, seats, hockey stick interior armrests, the list goes on. It is an interesting irony that the company that benefitted most heavily from the class that the Rover P6 created, chose to pay homage by signing off the last Rover created under their watch with so many P6 design cues.